- Free Initial Consultation: (954) 761-3641 Tap Here To Call Us

Sanon v. City of Pella – Drowning Litigation May Proceed

Swimming pools in Florida, by law, must abide by certain safety standards, whether they are residential or public.

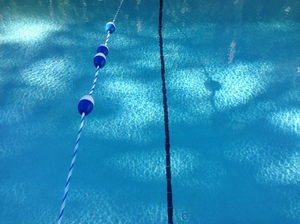

In the case of Sanon v. City of Pella, which was recently before the Iowa Supreme Court, the drownings of two non-swimmer teen boys at a public pool rented out for a private function was attributed at least partially to the fact the pool was murky and had no underwater lights – as required by law.

The question before the court was whether city employees’ decision to keep the lights off (due to rust, even though they still worked) and not provide any additional lighting to compensate met the criteria for the criminal offense of involuntary manslaughter. This critical distinction was necessary to overcome the city’s assertion of sovereign immunity that would bar any civil lawsuit against it for negligence. more Before delving into that case, let’s start by explaining the pool safety statutes in Florida. F.S.515.21 – 515.37 is known as the “Residential Pool Safety Act.” It was passed because drowning is the leading cause of death among young children in the state, and it’s also a significant cause of death for frail elderly persons.

Our Fort Lauderdale wrongful death lawyers know the purpose of the act is to reduce drownings by designing the pool and surrounding features to deny, delay or detect unsupervised entry into a swimming pool, spa or hot tub. Some of the provisions include requirements for proper gating, barriers, safety pool covers and alarm systems for when entry to a pool area occurs.

Meanwhile, F.S. 514.011 – 514.075 covers safety provisions relating to “Public Swimming and Bathing Facilities.” There are a number of exemptions, but essentially, the goals are similar to that of the residential pool act, and include provisions for gating, lighting and automatic shut-off systems.

In the Sanon case, a public pool area was rented out to a private camp function for one hour at night, between 8:30 p.m. and 9:30 p.m. Approximately 175 campers were present, including decedents, who were 14 and 15. Neither could swim, and their parents signed a waiver indicating as much, but that information was not relayed to the city’s lifeguards.

The two boys each took a slide down into the deep end of the pool, but did not reemerge – a fact lifeguards overlooked. The water was murky. The underwater lights were turned off, as per the direction of two city department supervisors after they found the light rims were rusted, although still functional. The boys were not found until the organization did a head count before leaving. They did not survive.

Parents sued the city for negligence, but the city claimed sovereign immunity, a protection given to most government entities in tort cases. However, there are usually exemptions, which vary state-to-state and depend also on the nature of the incident. Here, the case could only move forward if the parents could show the city worker’s actions were criminal – even though they had not been charged with a crime.

Trial court granted defense summary judgment motion and appeals court affirmed. But the state supreme court reversed. While the court stopped short of saying the worker’s actions were criminal, it did find there was enough evidence to make this determination, and the trial court should have carefully considered that before granting summary judgment to defense.

Call Fort Lauderdale Injury Attorney Richard Ansara at (954) 761-4011. Serving Broward, Miami-Dade and Palm Beach counties.

Additional Resources: Sanon v. City of Pella, June 26, 2015, Iowa Supreme Court More Blog Entries: Browning v. Hickman – Pretrial Investigation Critical in Crash Lawsuits, June 30, 2015, Fort Lauderdale Wrongful Death Attorney Blog